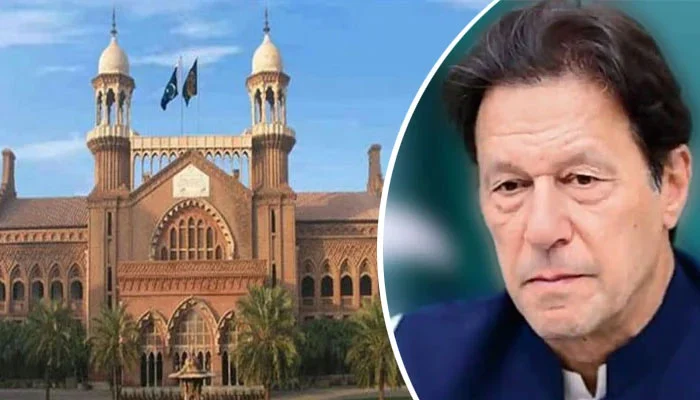

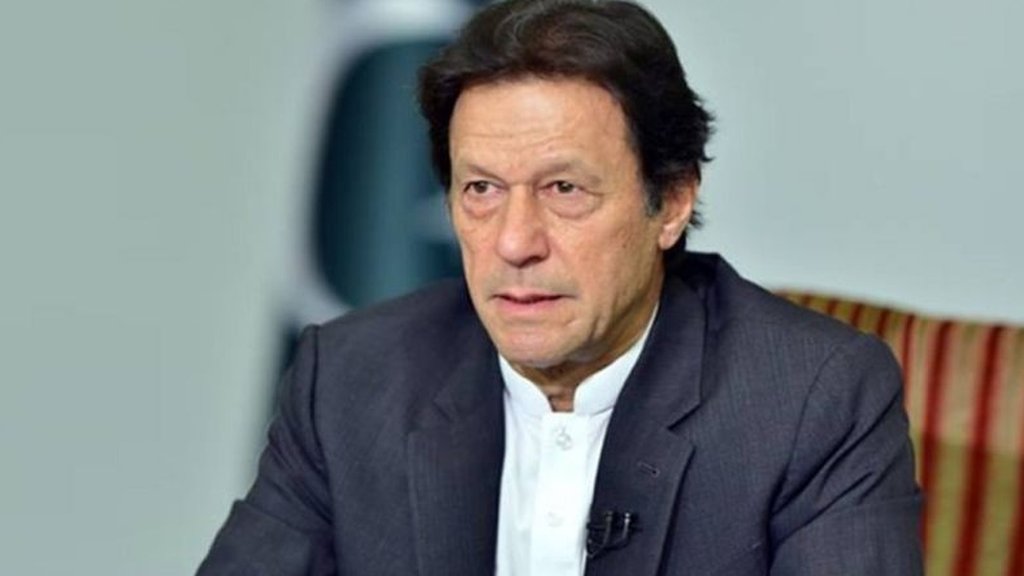

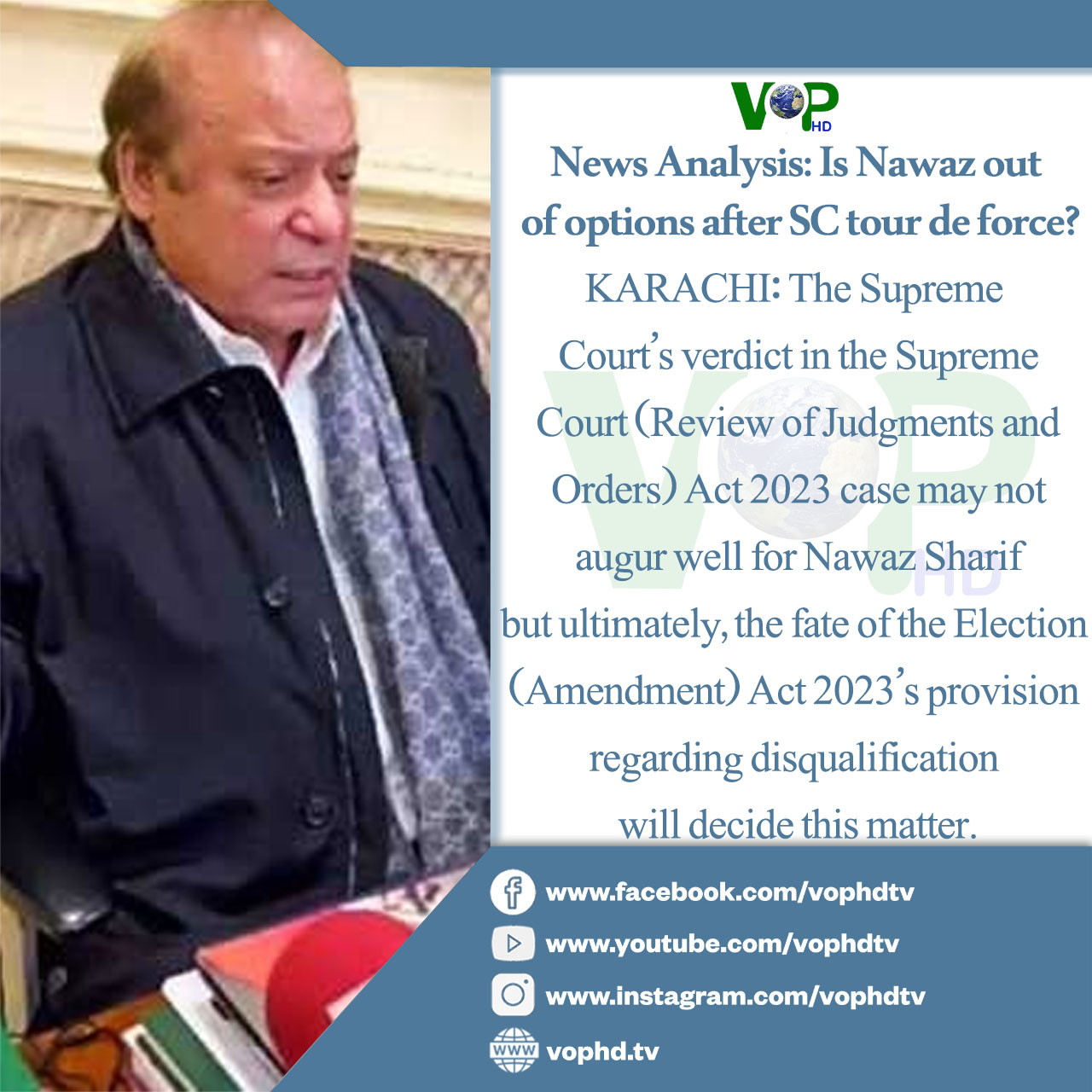

News Analysis: Is Nawaz out of options after SC tour de force?

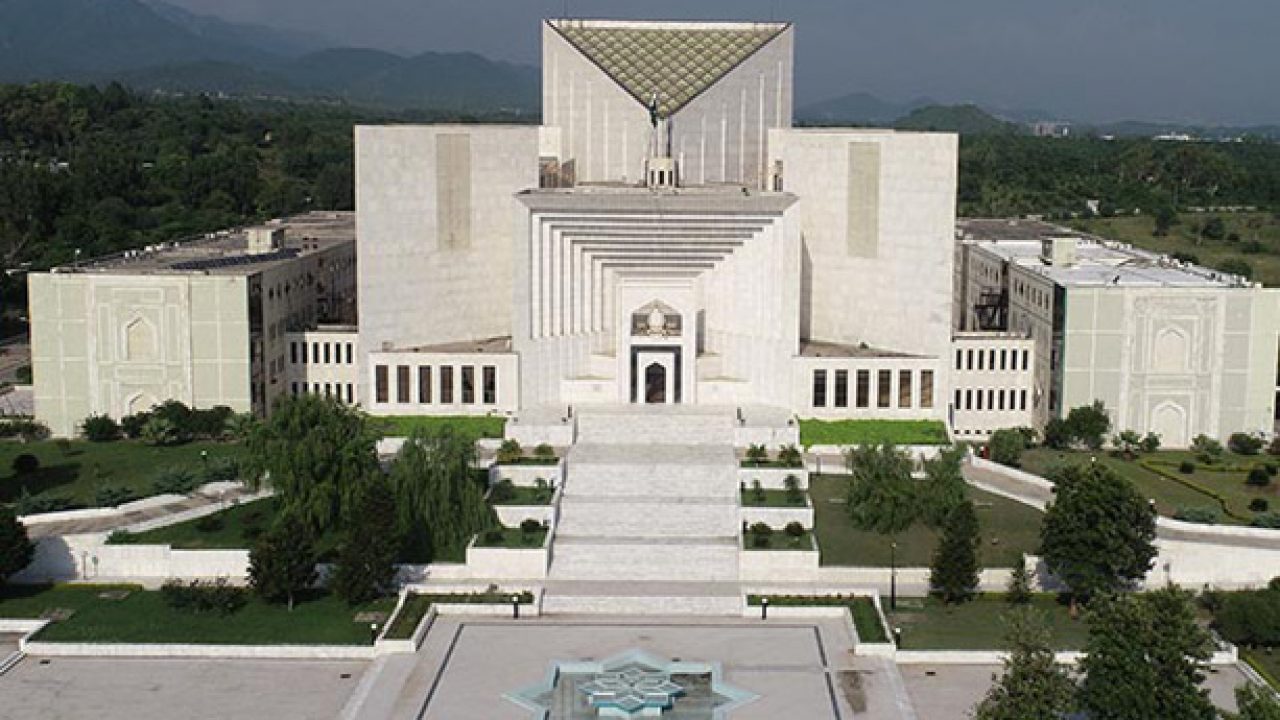

KARACHI: The Supreme Court’s verdict in the Supreme Court (Review of Judgments and Orders) Act 2023 case may not augur well for Nawaz Sharif but ultimately, the fate of the Election (Amendment) Act 2023’s provision regarding disqualification will decide this matter.

Legal experts reading the verdict in the SC Review Act say that while the verdict gets the differentiation between a review and an appeal right, it disregards the gaps the law was trying to fill.

Lawyer Abdul Moiz Jaferii elaborates: “I think the court disregards completely how the legislation attempting to enhance the scope of review was brought to try and fill a gaping void of the court’s own creation. In trying to give extraordinary sanctity to its own rule-making power as being drawn from the constitution, the court ignores how that power is subject to the law when stating it cannot be fettered by ordinary legislation.”

Barrister Rida Hosain, however, feels that “It was right for the Supreme Court to strike down the law. The law gave a ‘review’ with the scope of an ‘appeal’ against judgments of the Supreme Court handed down under Article 184(3) of the constitution. A review and an appeal are fundamentally different.” On this point, Supreme Court advocate Basil Nabi Malik too feels that “a review is a review and an appeal is an appeal and one can not be made into the other by mere ordinary legislation. Although pretty apparent, the said Act seemed to collapse the difference between the two, and that is precisely what the judgment attacks.”

There has been much talk about whether this verdict could impact the return of Nawaz Sharif to active politics. Jaferii feels Nawaz will not be able to appeal his disqualification for life “unless the incoming chief justice makes the adequate changes in the now hallowed Supreme Court Rules 1980 and allows for an appeal from the farce of a decision he was subject to.” According to him, the Election Amendment Act, 2023 does not provide Nawaz a respite since his disqualification “was rendered after the court interpreted a constitutional provision to hold a lifetime ban, and until that provision remains on the books or that judgment is reviewed, Nawaz remains disqualified for life. You would have to remove the article itself by way of a constitutional amendment. Or by incoming CJ Justice Qazi Faez Isa changing the Supreme Court Rules to allow for a second review.”

There is another view regarding this. Special Correspondent at Geo TV Abdul Qayyum Siddiqui says that while “the Samiullah Baloch judgment did hand down a lifetime disqualification to Nawaz, the Election Act amendment law is intact.” He is echoed in this by Supreme Court Correspondent for the Express Tribune Hasnaat Malik who says that “The Election Act amendment law has not been challenged. This is very surprising since the PTI’s legal team has been challenging every law but somehow hasn’t gone after this one; even the CJ hasn’t touched this law…and unless the law is challenged in court, it’s still in play.”

According to Hosain, while “there is dispute about whether the lifetime disqualification can be undone through simple legislation, regardless, once a law has been passed by parliament in the manner set out in the constitution, it must prevail. Unless it has been set aside or suspended by a court, it remains the law of the land.”

For High court advocate and former faculty at LUMS Hassan Abdullah Niazi, Nawaz’s fate will ultimately come down to “the amendments to the Election Act and how the Supreme Court interprets them. When the Supreme Court authored its lifetime disqualification judgment there was no clarity as to what the period of disqualification was supposed to be under Article 62(1)(f), so a reasonable interpretation would be that now that parliament has provided this clarity the Supreme Court should defer to this interpretation. However, the Supreme Court could also plausibly argue that once it has given a judgment, then either a constitutional amendment or a decision by a larger Supreme Court bench can overturn it”.

For Malik, “The Supreme Court has interpreted Article 62(1)(f) in a manner whereby its effects are permanent in nature, and as such, a simple amendment in the Election Act, 2017 may not be sufficient to undo it. If anything, this matter will inevitably end up back in court.” Siddiqui is of the opinion that “If Nawaz returns there is no bar on him; he has served his five year disqualification. If there is a dispute then a challenge can arise and yes it can end in litigation again.”

Siddiqui also brings up how the verdict talks about the supremacy of the Supreme Court Rules, 1980. He asks: “How can the SC 1980 Rules be superior to the constitution? That is odd. The verdict makes it seem like the 1980 rules are the constitution!”

The court seems to have disregarded the fact that “these rules which were supposedly the ground stone of independent judicial thought are more than four decades old and hopelessly outdated”, says Jaferii, adding that “there have been calls from within the court itself to answer for the issues created by adventurism through original jurisdiction. The bars have asked for it. Judges have ordered betterment but when parliament tries to do it, all we see is the Supreme Court jealously guarding territory it has itself left untended.”

For Niazi, “the problem with the judgment is that Article 188 of the constitution states that this power is to be exercised ‘subject to the provisions of any Act’ of parliament. Article 191 says that the Supreme Court can make rules to govern its procedure but this too is ‘subject to the constitution and law’.” Taken together, says Niazi, “it appears that the constitution envisions that parliament has the power to elaborate on how the Supreme Court’s review jurisdiction is to be exercised through ordinary legislation….This is what the SC review law was trying to do.”

On the verdict’s pronouncement regarding the SC Rules, Niazi says that: “the argument that the Supreme Court Rules, 1980 cannot be amended through ordinary legislation is problematic and finds no basis in the constitution. If this were true, why would the constitution specifically say in Article 191 that the Rules were to be subject to law?”

For Hosain, though, the SC review law not only went “beyond the legislative competence of parliament” by trying “to do through a simple majority what requires a two-thirds majority” but also had retrospective effect. “Per the majority judgment, this would open the floodgates, and allow review petitions to be filed regardless of when the decision was given. This would erode the finality of decisions of the Supreme Court.”

Hassan A Niazi’s reading of the verdict also shows that the court dismissed the attorney general’s argument that the law was needed on due process grounds. “I think that while addressing this point, the Supreme Court did not consider the broader context of how it has exercised its suo-motu power in the recent past. When the chief justice takes suo-motu notice he becomes almost like a party to a case and this raises serious concerns regarding impartiality. The only remedy to a decision taken in the Supreme Court’s suo-motu jurisdiction is a review heard before the exact same bench. This state of affairs raises genuine due process concerns that the SC review law sought to remedy.”