How India allowed RP-Sanjiv Goenka firms to beat coal auctions

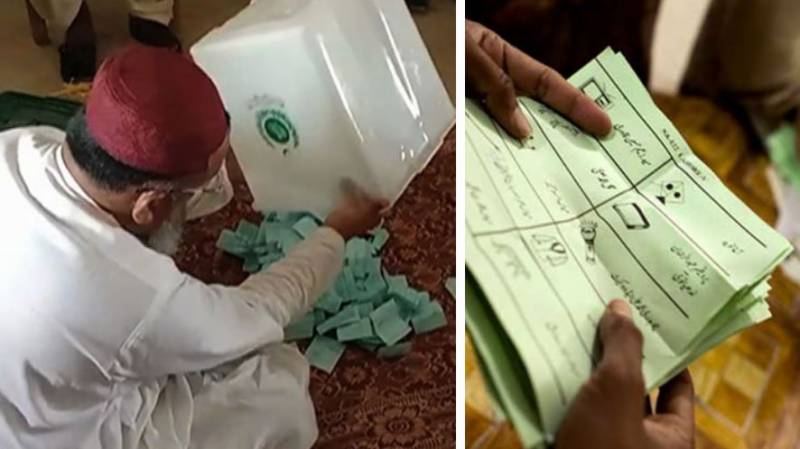

New Delhi, India – At 11am on January 31, 2015, India’s Ministry of Coal started the online bidding for the Sarisatolli coal mine in the eastern state of West Bengal. But it did not generate heat in the energy-hungry nation, and the first bid came one hour and 37 minutes later from a conglomerate’s firm. Of the five companies that were eligible to compete, only one kept sparring with the firm. Another made a fleeting appearance once and the rest did not bid.

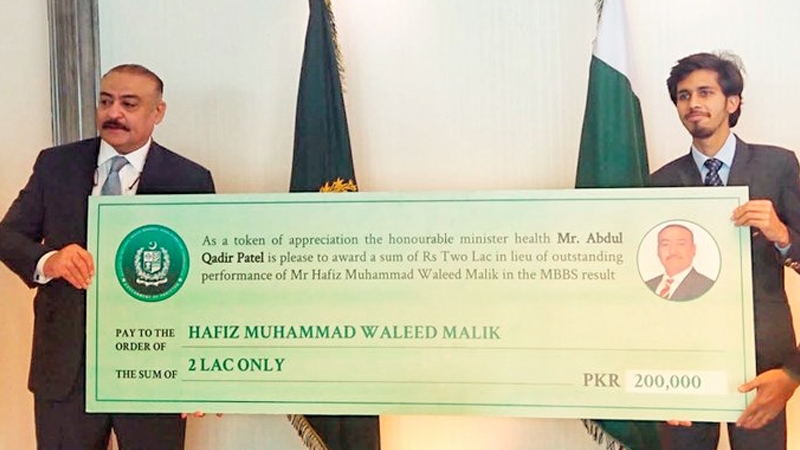

Three of those five bidders, including the winner, belonged to the same conglomerate, the RP-Sanjiv Goenka (RPSG) group, previously undisclosed internal documents of India’s top auditor, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG), reveal. The group is a $4bn-revenue conglomerate with interests in power, IT, education, retail and media.

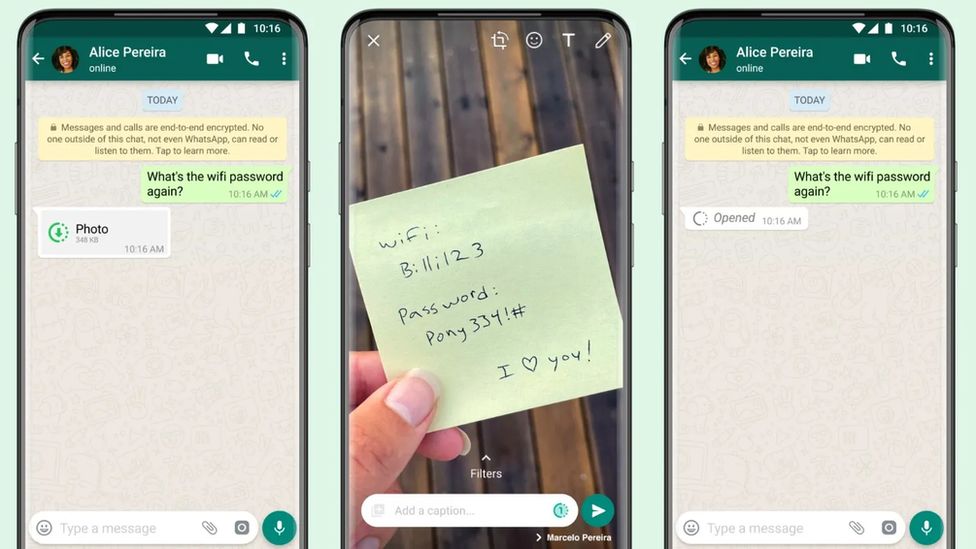

Of the three RPSG subsidiaries, the documents showed, one did not bid at all. Another subsidiary, a shell company the group acquired two days before the auction, tendered a bid from the same private internet protocol (IP) address used by its parent company and the bid-winner, the Calcutta Electricity Supply Corporation (CESC).

The documents indicated a lack of bid secrecy, essential for getting optimum value during an auction. Related entities participating and communicating with each other during the bidding process is widely considered to be “bid-rigging,” per CAG’s protocols.

CESC had the licence for the Sarisatolli mine until 2014 when India’s Supreme Court cancelled it, along with licenses for 203 other mines. Earlier governments, the court found, had handed out licences illegally and at a pittance, part of an alleged $22bn coal scam. The Narendra Modi-led BJP government that rode into power on an anti-corruption wave that year set out to “transparently” re-auction the mines through an electronic bidding process.

The first part of our investigation reveals that the new administration enabled private corporations to continue to bypass the competitive process to corner large coal reserves, ignoring several warnings from its auditors of loss to the government exchequer, as it had under previous governments.

The Sarisatolli mine was part of the first lot of auctions the Modi government conducted to hand over the coal reserves to private companies. The CAG officials red-flagged its auction and that of 10 other mines to the government in its final report on electronic auctions of coal mines submitted to Parliament in August 2016. It said the “potential level of competition” was not achieved during the auctions — a bureaucratic euphemism for failed auctions.

An auction is considered successful when different businesses compete to get an asset by bidding what they think is the fair value for it without being aware of the offers their competitors have made. In a true competition, the highest bidder gets the asset and the seller receives a fair market price. In this case, it seems this did not happen because some companies may have colluded through their subsidiaries to artificially lower the bids being offered for the coal block.

CAG’s final report listed the auctions for these 11 mines in which some bidders participated along with their sister firms. Apart from the RPSG Group, the other bidders that employed similar practices were Aditya Birla Group’s Hindalco Industries Limited, Vedanta’s BALCO and OP Jindal Group’s Jindal Power Limited (JPL).

Although CAG had evidence of RPSG companies bidding from the same IP address for the Sarisatolli mine, it only detailed their modus operandi in a “case study” to demonstrate the potential collusion without their identifiable details. It did not disclose the name of the mine or the identities of the bidders in the case study.