Power and Governance

Pakistan: A Political History

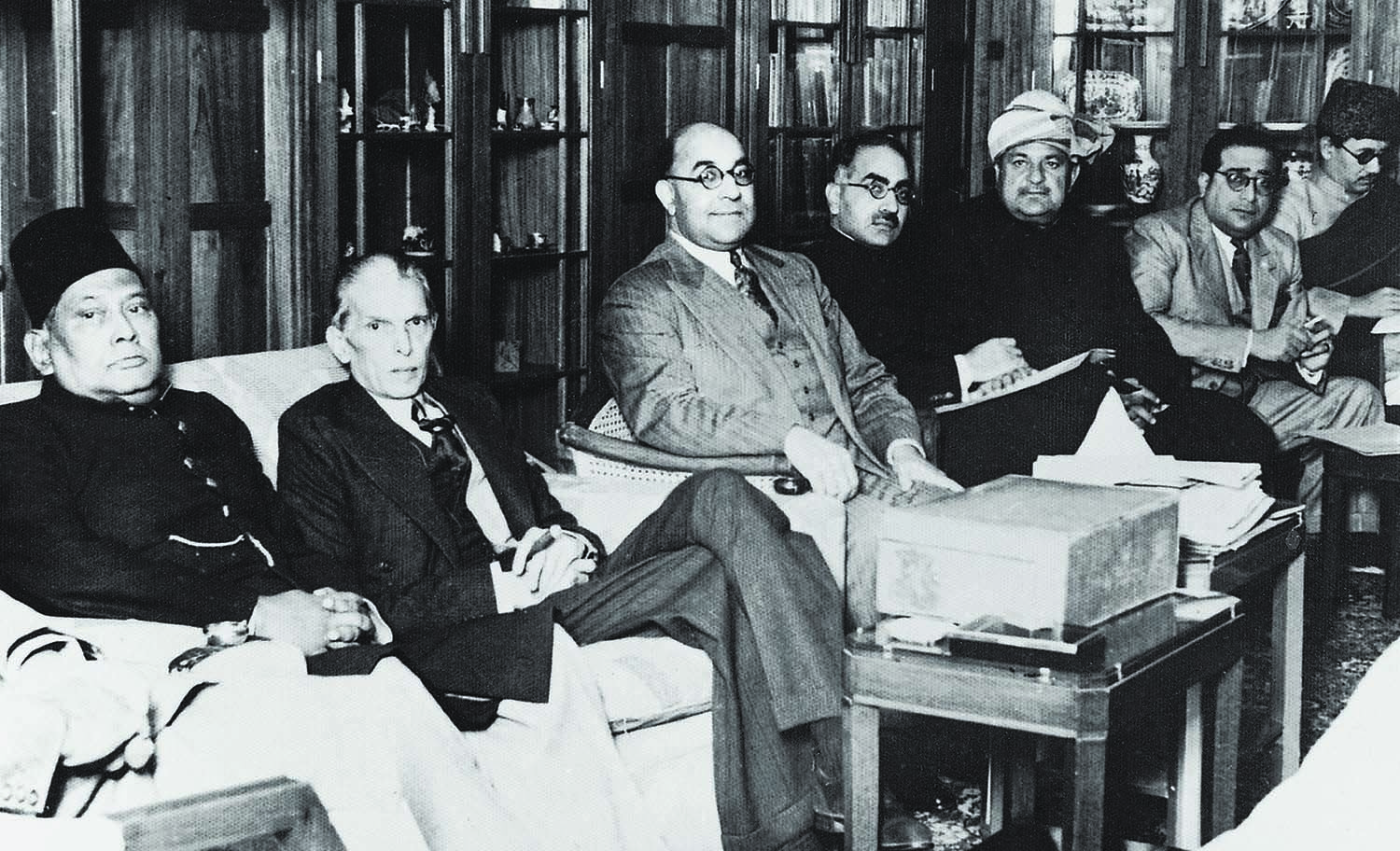

Both the military and the civil bureaucracy were affected by the disruptions wrought by partition. Pakistan cycled through a number of politicians through their beginning political and economic crises. The politicians were corrupt, interested in maintaining their political power and securing the interests of the elite, so to have them as the representative authority did not provide much hope of a democratic state that provided socio-economic justice and fair administration to all Pakistani citizens. Ranging controversies over the issue of the national language, the role of Islam, provincial representation, and the distribution of power between the center and the provinces delayed constitution making and postponed general elections. In October 1956 a consensus was cobbled together and Pakistan’s first constitution declared. The experiment in democratic government was short but not sweet. Ministries were made and broken in quick succession and in October 1958, with national elections scheduled for the following year, General Mohammad Ayub Khan carried out a military coup with confounding ease.

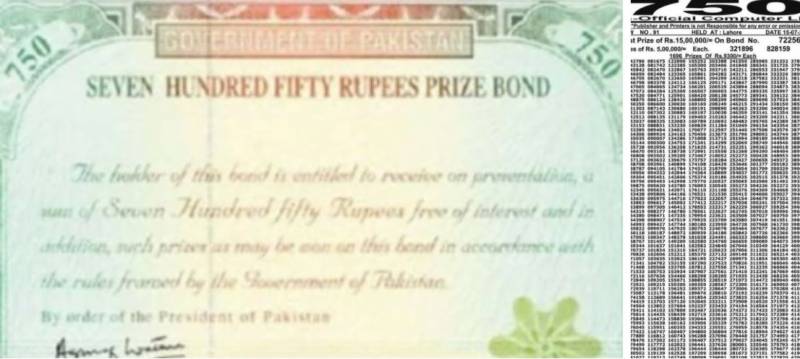

Between 1958 and 1971 President Ayub Khan, through autocratic rule was able to centralize the government without the inconvenience of unstable ministerial coalitions that had characterized its first decade after independence. Khan brought together an alliance of a predominantly Punjabi army and civil bureaucracy with the small but influential industrial class as well as segments of the landed elite, to replace the parliamentary government by a system of Basic Democracies. Basic Democracies code was founded on the premise of Khan’s diagnosis that the politicians and their “free-for-all” type of fighting had had ill effect on the country. He therefore disqualified all old politicians under the Elective Bodies Disqualification Order, 1959 (EBDO). The Basic Democracies institution was then enforced justifying “that it was democracy that suited the genius of the people.” A small number of basic democrats (initially eighty thousand divided equally between the two wings and later increased by another forty thousand) elected the members of both the provincial and national assemblies. Consequently the Basic Democracies system did not empower the individual citizens to participate in the democratic process, but opened up the opportunity to bribe and buy votes from the limited voters who were privileged enough to vote.

By giving the civil bureaucracy (the chosen few) a part in electoral politics, Khan had hoped to bolster central authority, and largely American-directed, programs for Pakistan’s economic development. But his policies exacerbated existing disparities between the provinces as well as within them. Which gave the grievances of the eastern wing a potency that threatened the very centralized control Khan was trying to establish. In West Pakistan, notable successes in increasing productivity were more than offset by growing inequalities in the agrarian sector and their lack of representation, an agonizing process of urbanization, and the concentration of wealth in a few industrial houses. In the aftermath of the 1965 war with India, mounting regional discontent in East Pakistan and urban unrest in West Pakistan helped undermine Ayub Khan’s authority, forcing him to relinquish power in March 1969.