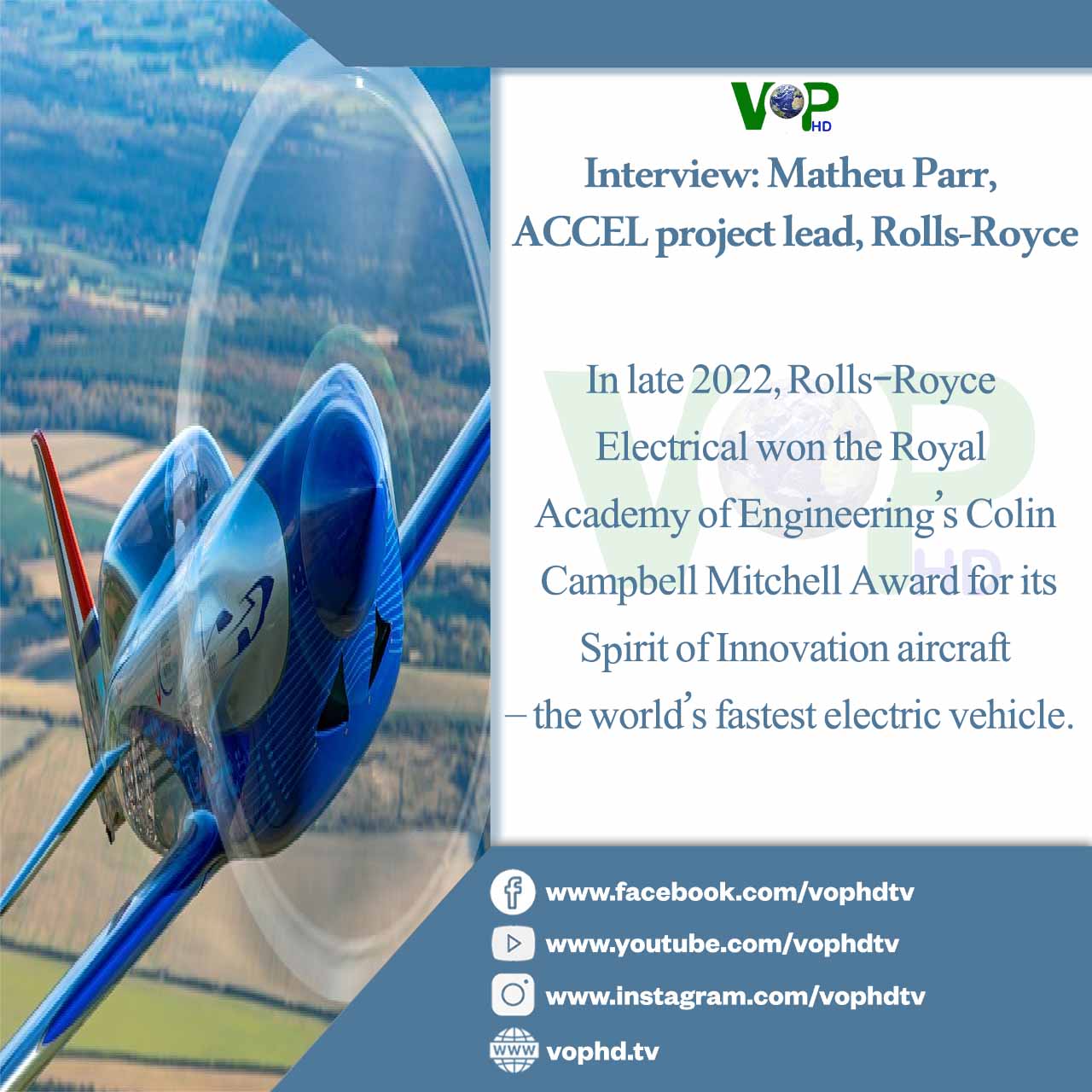

Interview: Matheu Parr, ACCEL project lead, Rolls-Royce

In late 2022, Rolls-Royce Electrical won the Royal Academy of Engineering’s Colin Campbell Mitchell Award for its Spirit of Innovation aircraft – the world’s fastest electric vehicle. Project lead on the ACCEL project and customer director Matheu Parr reflects on the technical achievement.

Describing the event as “a momentous occasion” and an “incredible achievement”, Matheu Parr recalls how Rolls-Royce Electrical’s demonstrator aircraft Spirit of Innovation set three world records. On 16 November 2021 the ACCEL (short for Accelerating the Electrification of Flight) project delivered top speeds over distances of 3km and 15km, and for the fastest 3,000m climb. With the records verified by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, the aircraft reached a top speed of 623km/h (387.4mph), making it the world’s fastest all-electric vehicle.

The success of the government-backed project prompted the then UK business secretary Kwasi Kwarteng to state that Spirit of Innovation would help to make electric flight part of everyday life, while stimulating the production of “cleaner, greener aircraft which will allow people to fly as they do now, but in a way that cuts emissions”.

Project lead for Spirit of Innovation and now Rolls-Royce Electrical’s customer director, Parr explains how the aircraft was propelled on its record-breaking runs by a 400kW (500+hp) electric powertrain, and the most power-dense propulsion battery pack ever assembled in aerospace: 6,480 cells producing enough power to charge 7,500 mobile phones.

In recognition of the ACCEL project team’s achievement it was awarded the Royal Academy of Engineering’s 2022 Colin Campbell Mitchell Award for making an “outstanding contribution to the advancement of any field of UK engineering”. Accepting the award, Chartered Engineer Parr stated that, “the electrification technology and capabilities that were developed are already being applied to create exciting new applications in the advanced air mobility market. I hope the records set by this fantastic aircraft inspire people to enable net-zero aviation.”

Parr says that Rolls-Royce Electrical is all about championing these technologies to bring about cleaner air travel for an urban population that will increasingly come to rely on flight for travelling across cities and on short commuter routes for work and recreation purposes. The industry uses the umbrella term ‘advanced air mobility,’ underneath which sits urban air mobility (UAM) and commuter aircraft. The future of these sectors lies in all-electric flying, “which is quieter, efficient and enables us to dramatically reduce travel times”.

The timeline for introduction of all-electric and hybrid-electric aircraft is “incredibly exciting” he says. “The technology is moving very fast. We are looking at bringing our batteries and motors into urban air taxis in 2026.”

The market is also accelerating: in the US, companies such as Joby and Archer already have air taxis they are looking to certify in 2024, aiming to bring them into commercial operation in 2025. The buzzword already being used is ‘jet zero’ and anyone thinking that urban air taxis are the stuff of sci-fi or the status symbol of the corporate CEO, rock star or hedge fund manager can think again. This is because, as Parr says, the technology will pass along energy-derived economies to all consumers, who can expect short-range air travel to start in the price-range of executive automobile services.

“Because of the way we’re using electricity to fuel the aircraft, we’re also targeting lower operating costs,” he explains. Coming in at around $4 per passenger-mile, air taxis are “similar in cost” to the Uber Black premium car service. Meanwhile, “as autonomy comes through to the market, we’re looking to bring the costs down similar to a conventional Uber. So there’s a push to get these aircraft into the premium market. But then we’re looking at how we can open this as a true mobility option for moving around in our day-to-day lives.”

According to Parr, Roll-Royce Electrical’s fundamental belief is that consumer commuting options will trickle down from the Spirit of Innovation demonstrator: “It isn’t just for high-net-worth individuals.” The market that the technology is reaching for will be equivalent to the helicopter market “by about 2030, and we refer to this as our initial market-entry phase”. After 2030, the business is looking at a target to surpass helicopter production volume, “and really starting to change the way people travel”. But there will be limits on the range, which is dictated “effectively by the chemistry in the batteries. So while the maximum range of these aircraft when they enter into service is initially going to be about 100km, the expectation is that most journeys are going to be much shorter than that – about 30-40km, as people try to move either from airports into cities or across cities.”

Rolls-Royce is currently working with Norwegian regional airline Wideroe, which “will be the launch customer for the P-Volt, an all-electric powered nine-seat fixed wing Tecnam aircraft, ready to enter service in the late 2020s. This will be using all-electric technology to power short flights where the geography lends itself to such zero-emission flights.”

As battery technology develops, the range will increase, opening up markets in which these aircraft can operate. “This is why we are also developing new turbogenerator technology specifically for the advanced air mobility market. It will be designed for hybrid-electric applications and will have scalable power offerings. As an on-board power source, it will complement the Rolls-Royce electrical propulsion portfolio, enabling extended range on sustainable aviation fuels and later, as it comes available, through hydrogen combustion.”

One of the effects of changing consumer habits ushered in by battery-powered air commuting is that the urban air mobility market will transform the way airports are used, especially in the area of charging infrastructure. “This includes applying Rolls-Royce Power Systems-developed climate-friendly microgrids that combine renewable energy sources, battery storage and conventional power generation to charge the aircraft systems. Soon we will also offer them with fuel cell generators, hydrogen engines and electrolysers.”

As energy density improves, “we will be able to start to double the range of the aircraft”, but forecasts for powering larger passenger aircraft with batteries remain in the future. What’s needed to take us on our holidays isn’t going to be achievable: “As flight times and aircraft sizes increase, then you start to move into the application of more electric engine technology alongside sustainable aviation fuel in the short term and hydrogen in the longer term.”

Parr explains that while Spirit of Innovation was in development, Rolls-Royce “worked alongside airframer Tecnam and manufacturer Rotax to complete the flight-testing of a hybrid-electric aircraft, powered by a parallel-hybrid propulsion system. This introduced advanced technology for a smaller power class and is potentially scalable to larger aircraft.”

The organisation also provided the propulsion system to Airbus for the world’s heaviest urban air mobility demonstrator, which completed its flight test programme in 2021. “These are demonstrations of incredible technical achievements, but they crucially also provided important data and capabilities that we will be applying to products that will be powering aircraft in the near future.” An example of how this knowledge can be applied to other projects is that the UAM battery requirements are similar to those developed for the Spirit of Innovation record runs.

One of the benefits of air taxis, says Parr, is that compared with helicopters, electric-powered air taxis are a thousand times safer. “When we talk about developing UAM aircraft, we’re also talking about targeting safer operating levels where we go from 10-6 – one failure every million hours – to 10-9, which is what you get in large civil aircraft.” This is in part due to the distributed architecture: “The aircraft will look different. More propellers, which means that we can run them at slower speeds while generating less noise.”

Parr acknowledges that the batteries in the energy storge system are heavy, which means that they’ve been integrated into the overall design “as close to the centre of gravity as possible”. In contrast to conventional aircraft, where aviation fuel is stored in the wings with its weight reducing over the course of the flight, “we have had to put the batteries into the fuselage”, on a template similar to the design of an electric car, where everything is put onto a ‘skateboard’ that sits underneath.

Thought was also given to the way in which the electrical propulsion distribution system is set up, which is “driven around safety and noise”. Parr explains how Nasa studies show that electric aircraft are “effectively a third quieter than a helicopter when it’s on the pan and ready to take off. And we’re a thousand times quieter than a helicopter in the air over the city.” They’re also cleaner, with no emissions while in flight. “One of the biggest pushes in the industry, and one of the things I’m often asked about these aircraft, is ‘what is the second-use life of the batteries that come out the aircraft? How are we going to recycle them? How are we going to ensure we’ve got a full-life-cycle sustainability mission?’ I don’t think that anyone’s going to accept these batteries not having a sustainable option for how they are going to be re-used.”

Returning to the Colin Campbell Mitchell Award, Parr says that there’s a personal significance attached to its origins. When he joined Rolls-Royce as an electrical engineer “many years ago”, he worked initially on the group’s Brown Brothers site in Dunfermline, where the legendary Commander C C Mitchell worked, “so there’s a close connection to me”. He reminds me that it was another Mitchell – this time Reginald ‘R J’ Mitchell of Supermarine Spitfire renown – who “also inspired us on the project. A lot of our team ethos came out of that period of air racing in the 1920s and 1930s, when there were small teams trying to demonstrate what their technology could achieve.”

When Spirit of Innovation set out to test what could be done with electrification “we kept a lot of their principles, bringing in people who were dedicated experts in their area while also being focused on the competition. So the award is a great recognition of the engineering involved.”

In fact, Rolls-Royce has a strong tradition of attempts at flying speed records, dating back to the Schneider Trophies of the early 1930s. The speed achieved by test pilot and Rolls-Royce director of flight operations Phill O’Dell in the Spirit of Innovation was more than 213km/h (132mph) faster than the previous record set by the Siemens eAircraft powered Extra 330 LE Aerobatic aircraft in 2017. Never before in the history of the World Air Sports Federation record attempts has there been such a significant increase in speed over such a short timeframe, highlighting the rapid pace at which the electrification of aerospace is advancing.

At the time, O’Dell said: “Breaking the world record for all-electric flight is the highlight of my career and an incredible achievement for whole team. The opportunity to be at the forefront of another pioneering chapter of Rolls-Royce’s story, as we look to deliver the future of aviation, is what dreams are made of.”

As a final thought, Parr recalls that while studying engineering at the University of Sheffield in the early 2000s “a representative of the IET came along to inspire us to join the organisation. And I think today that this project will also help to inspire people to start a career in aviation. And there’s a whole host of resources that we’ve put together to help people not only at university level but also at primary schools. And so I’d like to push the fact that I think these sorts of projects are great, not just in the technical demonstration, but in the way we can inspire the next generation of engineers and scientists.”