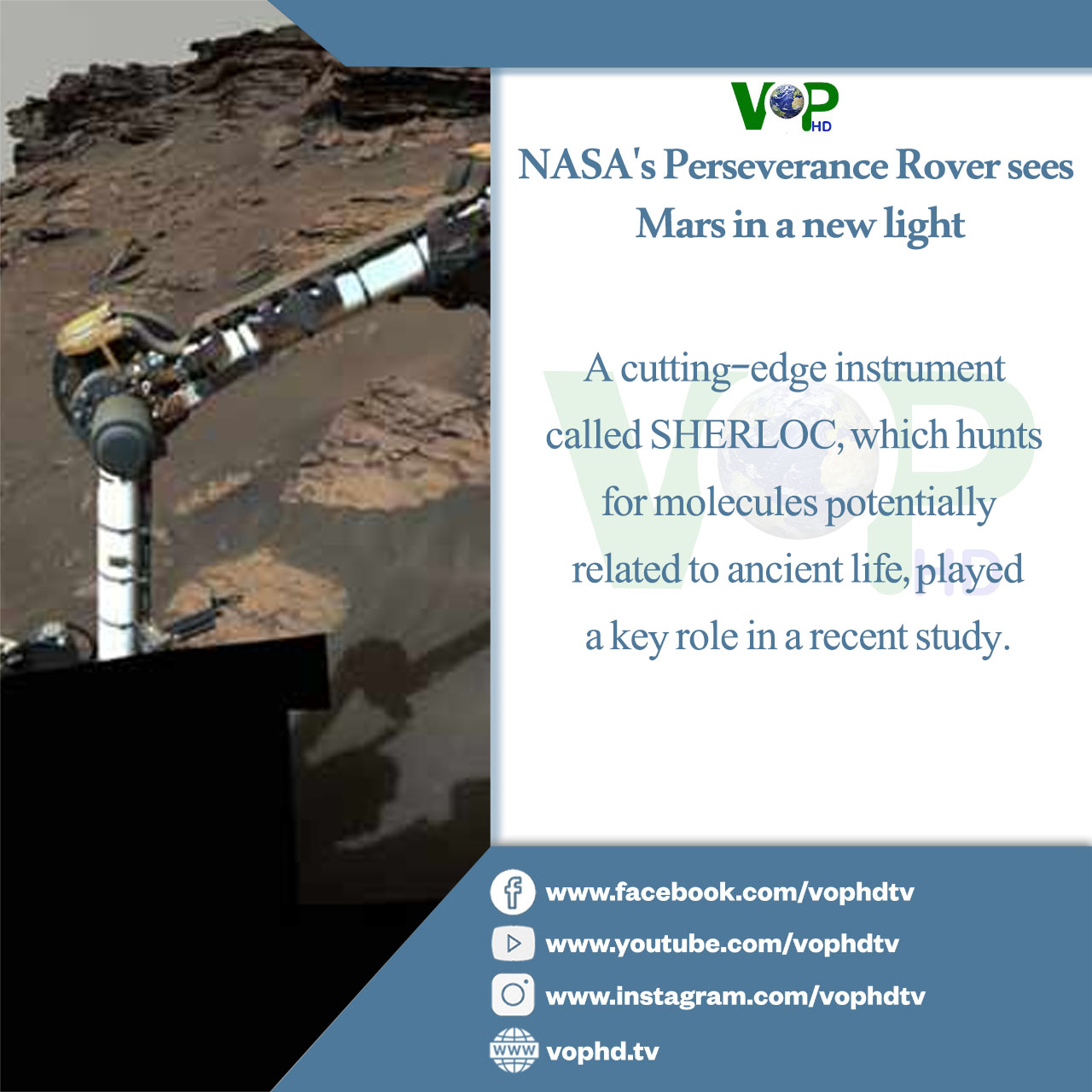

NASA’s Perseverance Rover sees Mars in a new light

A cutting-edge instrument called SHERLOC, which hunts for molecules potentially related to ancient life, played a key role in a recent study.

In its first 400 days on Mars, NASA’s Perseverance rover may have found a diverse collection of organics – carbon-based molecules considered the building blocks of life – thanks to SHERLOC, an innovative instrument on the rover’s robotic arm. Scientists with the mission, which is searching for evidence that the planet supported microbial life billions of years ago, aren’t sure whether biological or geological sources formed the molecules, but they’re intrigued.

Short for Scanning Habitable Environments with Raman & Luminescence for Organics & Chemicals, SHERLOC helps scientists decide whether a sample is worth collecting. This makes the instrument essential to the Mars Sample Return campaign. The Perseverance rover is the first step of the campaign, a joint effort by NASA and ESA (European Space Agency) that seeks to bring scientifically selected samples back from Mars to be studied on Earth with lab equipment far more complex than could be sent to the Red Planet. The samples would need to be brought back to confirm the presence of organics.

SHERLOC’s capabilities center on a technique that looks at the chemical makeup of rocks by analyzing how they scatter light. The instrument directs an ultraviolet laser at its target. How that light is absorbed and then emitted – a phenomenon called the Raman effect – provides a distinctive spectral “fingerprint” of different molecules. This enables scientists to classify organics and minerals present in a rock and understand the environment in which the rock formed. Salty water, for example, can result in the formation of different minerals than fresh water.

After SHERLOC captures a rock’s textures with its WATSON (Wide Angle Topographic Sensor for Operations and eNgineering) camera, it adds data to those images to create spatial maps of chemicals on the rock’s surface. The results, detailed in a recent paper in Nature, have been as promising as the instrument’s science team had hoped.

“These detections are an exciting example of what SHERLOC can find, and they’re helping us understand how to look for the best samples,” said lead author Sunanda Sharma of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. JPL built SHERLOC along with the Perseverance rover.

NASA’s Curiosity rover, which landed on Mars in 2012, has confirmed the presence of organic molecules several times in Gale Crater, 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) away from Perseverance. Curiosity relies on SAM, or the Sample Analysis on Mars, an instrument in its belly that heats up powderized rock samples and performs a chemical analysis on the resulting vapor.

Because Perseverance’s scientists are looking for rocks that may have preserved signs of ancient microbial life, they want to leave the samples intact for closer study on Earth.

Getting to the Core

The new Nature paper looks at 10 rock targets SHERLOC studied, including one nicknamed “Quartier.”

“We see a set of signals that are consistent with organics in the data from Quartier,” Sharma said. “That grabbed everyone’s attention.”

When data that comes back from SHERLOC and other instruments looks promising, the science team then decides whether to use the rover’s drill to core a rock sample that’s about the size of a piece of classroom chalk. After analyzing Quartier, they took rock-core samples “Robine” and “Malay” from the same rock – two of the 20 core samples collected so far (learn more with the sample dashboard).

Picking out a good target to collect a sample from isn’t as simple as looking for the most organic molecules. Ultimately, Perseverance’s scientists want to collect a set of samples that’s representative of all the different areas that can be found within Jezero Crater. That breadth will provide context for future scientists studying these samples, who will wonder what changes occurred around any samples that might indicate signs of ancient life.

“The value comes from the sum rather than any individual sample,” Sharma said. “Pointillism is a good analogy for this. We’re eventually going to step back and see the big picture of how this area formed.”